Some think SPACs fill a market void left by a deficient IPO system but critics have called them a rip-off. Who’s right and what’s next?

by Paul Bryant

Between 2020 and 2022, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs), a decades-old concept, moved from occupying a small niche of initial public offering (IPO) activity to becoming the most common type of IPO in the US to experiencing a dramatic collapse.

Regulators have acted. Investors are rethinking. The future of SPACs hangs in the balance.

SPACs and their rationale

SPACs, often referred to as ‘blank cheque companies’, raise capital via an IPO and list on a stock exchange as a ‘cash shell’. Their founders, or sponsors, then have a window, typically two years, to find an unlisted ‘real business’ (a target company) with which to merge.

Once a target is found and a merger transaction negotiated (a de-SPAC), SPAC shareholders vote to approve or reject the deal, and have the right to redeem their shares – they can withdraw from the deal and get their money back, plus interest.

The result is the previously privately owned target company ends up as a publicly listed entity, with a cash injection from new investors.

For target companies, a de-SPAC can offer several attractions over a ‘traditional’ IPO, including a much faster route onto public markets; a higher valuation (IPOs are often underpriced, resulting in a price ‘pop’ on the first day of trading); and valuation certainty – this is negotiated with sponsors upfront as opposed to an IPO valuation which is subject to a long period of market risk as it is only set shortly before the IPO, 12–18 months after starting the process.

And according to Dr Daniele D'Alvia – author of the 2022 book Mergers, acquisitions and international financial regulation: analysing special purpose acquisition companies – for investors, especially retail investors, SPACs are an opportunity to gain exposure to late-stage venture-capital-type investments, which are mostly only available to institutions through private equity and venture capital funds.

Boom and bust

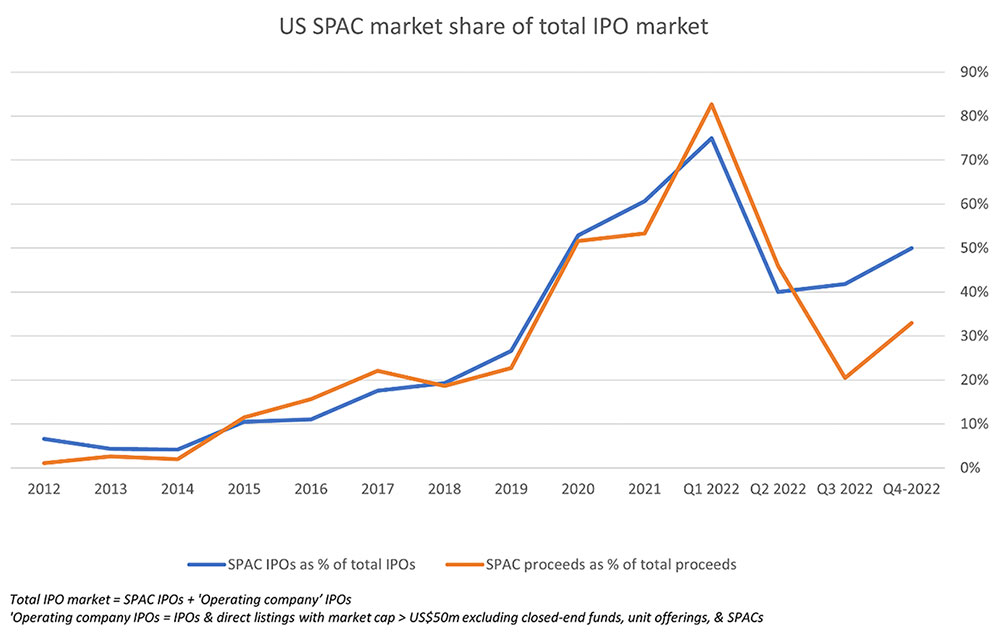

This apparent win-win structure for high-growth companies and adventurous investors gained the most traction in the US. Momentum gradually built in the decade after the global financial crisis, before SPAC activity took off in 2020 and 2021 (Chart 1), with the number of SPAC IPOs totalling 613 in 2021, more than ten times the number in 2019, according to data provider SPACInsider.

Chart 1

This dwarfed activity levels in other major capital markets. European stock exchanges recorded 39 SPAC IPOs in 2021 (16 in Amsterdam, six in London), up from just five in 2019, according to the January 2022 report by global law firm White and Case, European SPAC & de-SPAC data & statistics roundup. However, this was a nine-fold increase in the four listings in 2020. Meanwhile, Hong Kong and Singapore only recorded their first SPAC listings in early 2022, according to Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) and Singapore Exchange Limited (SGX).

But in 2021, the US SPAC market wobbled when the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) signalled it was considering stepping up regulation. In a statement released on 8 April 2021, the SEC says: “Concerns include risks from fees, conflicts, and sponsor compensation, from celebrity sponsorship and the potential for retail participation drawn by baseless hype, and the sheer amount of capital pouring into the SPACs.” In 2022, the SPAC market collapsed, in an even more dramatic fashion than the traditional IPO market (Chart 2).

Chart 2

High costs and conflicts of interest in the US

In their 2022 paper, A sober look at SPACs, Professor Michael Klausner of Stanford University and Assistant Professor Michael Ohlrogge of New York University report on their study of a sample of 47 SPACs.

They find that post-IPO investors are heavily impacted by three ‘costs’: 1) a sponsor equity incentive (or promote) of 20% of post-IPO, pre-de-SPAC equity; 2) warrants issued to sponsors and IPO investors (mostly hedge funds) which grant them a right to purchase shares at a price slightly above the IPO price, usually within five years; and 3) IPO underwriter (investment bank) and other fees.

These result in the SPACs not having US$10 per share (a SPAC IPO pricing convention) to invest in a target company, but a median ‘net cash per share’ of only US$5.70 (mean: US$4.10). Klausner told the CISI: “In its current form, a SPAC is just a rip off of retail investors who presumably do not know that they are paying US$10 to invest US$5 in a target company. It is like paying your broker a 50% commission. An investor that invests US$5.70 in a company can expect about that much value in return, and our research showed that indeed that is what SPAC investors received unless they redeemed their shares ”

Post-IPO investors are heavily impacted by three ‘costs’ In the report, Klausner et al also highlight that the 20% promote and other elements of the SPAC structure could incentivise a sponsor to execute a ‘bad de-SPAC deal’ over no deal at all. This is because the only way a sponsor realises an upside is to execute a de-SPAC and be left with their share of the combined entity (their 20% pre-deal share will dilute post-de-SPAC). Otherwise, it must liquidate and distribute its cash to shareholders, with the sponsor receiving nothing.

But sponsors do sometimes invest significant cash into deals, which strengthens their alignment with other shareholders. For example, Chamath Palihapitiya, founder and chief executive officer of Social Capital Hedosophia, which merged with Virgin Galactic, invested US$100m at the time of de-SPAC, according to a 2019 article by investment bank Renaissance Capital, 'The SPACe SPAC: everything you need to know about Virgin Galactic’.

Litigation picks up

Conflicts of interest have been central to an increase in SPAC-related litigation in the US, according to Nelly Ward Merkel, a trial lawyer who is representing several clients in SPAC litigation cases.

She says: “What is driving litigation is concern over whether the merger transactions really make sense, whether they were rushed (remembering that SPACs operate with a deadline to conclude a deal), and whether the valuations of target companies are justifiable. That usually comes down to issues around the fiduciary duty of the SPAC sponsors and directors, and it does look like deal structures and disclosures are playing a role in how courts scrutinise fiduciary duty.”

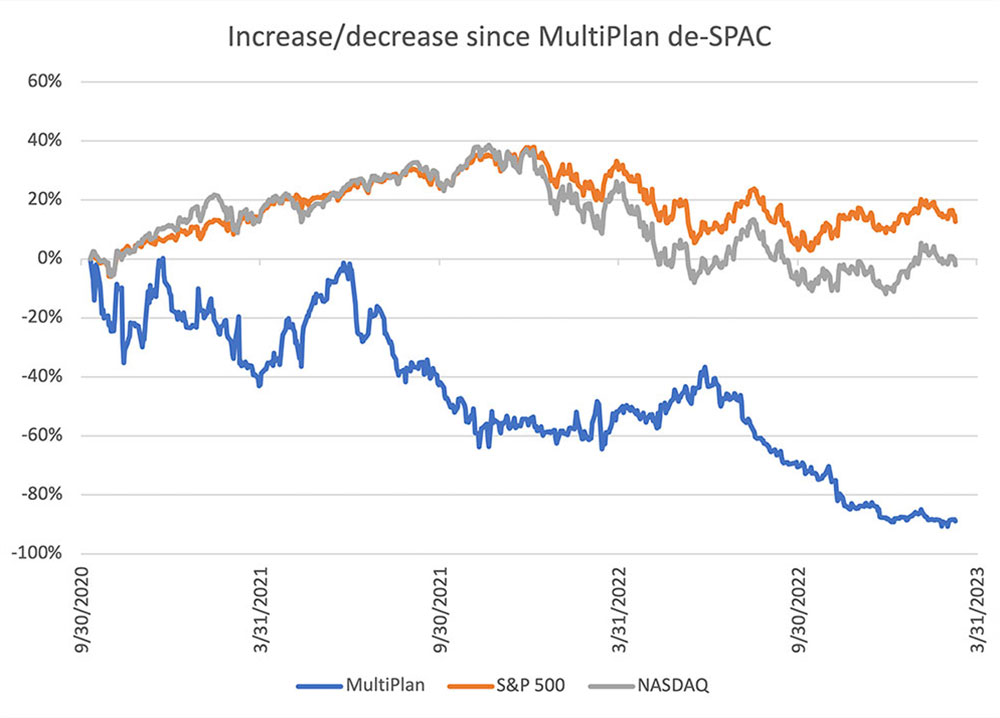

She cites the shareholder action against healthcare systems provider Multiplan Corporation as a potential landmark case. Several shareholders (plaintiffs) of the SPAC that merged with Multiplan allege that material information had been withheld from them, including that MultiPlan’s largest customer was building an in-house platform to compete with MultiPlan. MultiPlan subsequently filed a motion to dismiss the case in the Delaware Court of Chancery.

Vice Chancellor of the court, Lori Will, in her decision (called an opinion) on 3 January 2022, states: “The crux of the plaintiffs’ claims is that the defendants’ actions – principally in the form of misstatements and omissions – impaired [SPAC] public stockholders’ redemption rights to the defendants’ benefit.”

She rejects the motion to dismiss and rules that a heightened standard of review should apply to the case, primarily because the SPAC and de-SPAC transactions involved inherent conflicts, largely around the incentives associated with the founder’s shares.

The case was settled by MultiPlan before it went to trial. It paid US$34m, without admitting liability.

It’s been a disappointing investment for shareholders. Since the de-SPAC on 9 October 2020, the MultiPlan share price has fallen 89%, compared with a 10% fall in the NASDAQ index and a 10% rise in the S&P 500 (Chart 3 – as at 4 Jan 2023).

Chart 3

Regulators, lawmakers, and exchanges respond

In March 2022, the SEC proposed new rules (not yet in force) to enhance disclosure and investor protections.

Included are requirements for additional disclosures about conflicts of interest (tabular disclosure of all forms of sponsor compensation including contingent compensation upon conclusion of a de-SPAC transaction) and sources of dilution (a simplified tabular dilution disclosure on the prospectus cover page). It is also proposed the SPAC state whether it reasonably believes that the de-SPAC transaction is fair or unfair to investors.

In the EU, most legislation, regulations, and rules affecting SPACs (e.g. company law and stock exchange listing rules) exist at a country level so are not common across the bloc. However, in July 2021, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published a public statement containing guidance on prospectus disclosure and investor protection expectations of SPACs, seeking to promote uniformity across the EU.

The guidance has similar themes to the proposed US rules, but a key addition is that ESMA has highlighted that SPAC transactions may not be appropriate investments for retail investors and that firms should consider excluding them.

In the UK, new rules came into force in August 2021, detailed in an investor protection document which, probably most importantly, removes a legal quirk which had held back the UK SPAC market until then. Previously, a SPAC’s shares would be automatically suspended from trading when a de-SPAC deal was announced, locking in investors until the acquisition was completed or fell through.

HKEX in Hong Kong meanwhile adopted more restrictive rules in January 2022, including requirements that the de-SPAC transaction vote excludes the SPAC promoter and others (preventing potentially conflicted shareholders from participating in the vote), and that new investors in a ‘successor company’ are fully informed of any potential dilution before their investment.

Return to more sober market expected

Key SPACs facts

SPACs are also commonly known as ‘blank cheque’ companies.

They list on a stock exchange, raising money from investors, and have no commercial operations after listing, starting life on public markets as a cash shell.

A SPAC’s sole purpose is to find a target company with commercial operations to merge with, providing that company with an alternative to its own IPO.

SPACs are a faster route onto public markets for target companies and offer more valuation certainty for them too

Merging with SPACs has been most popular among earlier-stage, high-growth companies.

The US has been the epicentre of SPAC activity, with SPACs caught up in the pandemic retail investor boom of 2020, when they surged in popularity, then crashed.

They have been beset by controversy, often associated with conflicts of interest between their founders and investors, with significant litigation activity in the US.

SPAC regulation has changed or is changing in most major capital markets, and if SPACs make a comeback, it will be in a much more restrictive regulatory environment.

Professor Klausner thinks it is "most likely that SPACs in their current form are dead, as they should be”.

But while most other commentators see a bleak short-term outlook, over a longer time horizon, they are more positive. Dr D'Alvia says that more robust SPAC-specific regulation around the world will create more legitimacy, albeit in an environment of more regulatory rules and less flexibility.

Tim Stevens, a partner at law firm Allen & Overy, has advised several SPAC clients on their IPOs on the Euronext Amsterdam exchange. He says: “We recognise there is a lot of criticism of SPACs but much of that ignores why they are there in the first place. And that’s because the IPO route is just way too difficult for some companies, so unless the IPO route is made easier, then I think SPACs will make a comeback.”

But he sees a different market ahead: “Heavily sponsor-friendly terms will disappear; investors are onto that. And sponsors will probably be more specialist and experienced. SPACs can offer advantages in niche sectors such as biotech where the sponsor can bring scarce expertise to the table. It’s of huge value to investors if someone like that does the ‘first shift’ of due diligence.”

The London Stock Exchange sees SPACs occupying a niche area of listing activity, while Hong Kong looks like a market to watch. According to the executive director of the Hong Kong Financial Services Development Council (FSDC), Dr King Au, SPACs are seen as an important part of an intensive push to encourage the listing of companies from various markets, including high-tech companies, onto the HKEX.

Implications

For CISI members and their clients, SPACs, most probably in a more sober guise, may present opportunities to invest in the equity of earlier-stage, high-growth companies.

This is where the operational challenge for advisers will lie – in determining the appropriateness of these investments for clients. For some, certain SPACs may be a valuable addition to a portfolio. For others, because of their high-risk nature, they may be entirely inappropriate.

But what members and their clients can look forward to in most jurisdictions, because of more demanding disclosure requirements, is having more information available to make informed investment decisions. If the SPAC market recovers.