The cost to investors of the industry’s fees and charges has been a hot topic for some time. But what is the reality on the ground for investors?

by Dan Atkinson

Simmering discontent with what were often seen as unreasonable deductions from the value of clients’ funds intensified after the global financial crisis of 2007–8, when, too often, the level of charges seemed not to reflect the shrunken value of portfolios. Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic started to take a close interest, and new rules and guidelines were promulgated.

Those events themselves are now beginning to slip out of history’s rear-view mirror. So, what is the current position now, and has it changed for the better or not?

In a market insights report from September 2021 that looks at the costs of UCITS (Undertakings for the Collective Investment in Transferable Securities), the European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA) finds that the simple average cost of ownership of cross-border actively managed collective funds is 1.68%, breaking down into 1.96% for equity funds, 1.34% for bond funds and 1.76% for multi-asset funds.

The FCA found that asset managers in general fail to disclose all costs and charges, meaning they are insufficiently clear to investors Where does this money go? The report’s findings show that, on average, 41% of the fee charged by UCITS covers fund managers’ expenses relate to product development and investment management, 38% goes to distributors for advice and intermediary services, and the remaining 21% covers administration services, depositary, taxes and other expenses.

Commenting on the report’s findings, Bernard Delbecque, senior director for economics and research at EFAMA, and author of the report, says in a press release: “The fact that fund managers only retain on average 41% of the total cost paid by retail investors means that the largest part of the cost of UCITS borne by investors is used to finance fund administration, depositary and other services, taxes, distribution and advice.”

Putting costs in perspective

As one would expect, the report finds that index-tracking funds have lower costs than the actively managed variety, given the lower involvement required of fund managers. And that, overall, the charges represent a bargain.

The press release provides the following example: Had someone invested €1,000 at the end of 2009, split equally between an actively managed retail equity UCITS and an index-tracking equity UCITS, then on average, ten years later, they would be enjoying a net value of €2,530. The cost of this performance would have been a total of €76 to the fund manager, €76 to the distributor and €43 to the other service providers.

Delbecque puts these costs into perspective by comparing them to a "subscription to a typical digital music, podcast, and/or video service, which costs at least €9.99 per month, or €1,199 for ten years”.

In the UK, fund managers may well have awarded themselves a pat on the back in March 2022, when Morningstar, the investment research and management company, published its Global investor experience study, the first to be published since 2019. Morningstar's research shows UK fund fees to be among the lowest in the world, carrying a median cost of 0.83% for allocation, 0.84% for equity and 0.55% for fixed income. The report says that the UK has “lower asset-weighted median expense ratios [and] investor-friendly approaches to initial charges and ongoing commissions”.

True, Morningstar finds that fees were lower in the majority of the 26 countries it had studied compared with 2019, but the UK saw the most significant drop in fund costs. That year was something of a watershed for UK funds, given the publication in February 2019 of a review by the UK financial regulator, the FCA, into ‘disclosure of costs by asset managers’. Much of it will not have made comfortable reading for the sector.

Clear-out of charges

The review finds that most asset managers calculate transaction costs in accordance with the rules but some fail to disclose them prominently and clearly. Worse, asset managers in general fail to disclose all costs and charges, meaning they are insufficiently clear to investors. And even when full disclosures of costs are made, documents and websites are inconsistent, presenting an obstacle to client understanding.

“We conclude that asset managers may be communicating with their customers in a manner that is unfair, unclear or misleading and, as such, investors can be confused and misled as to how much they are being charged,” states the FCA.

That was more than three years ago. What has changed in the interim?

According to Dona Ardeman, partner at law firm Mills & Reeve, the industry’s response to the 2019 report was a clearing out of inappropriate charges. Funds are no longer charging due diligence fees – they are paying for due diligence themselves, she says. And they have stopped cross-charging clients for what they were doing anyway.

Global good practice

There remain glitches, however, not least in the volume of information now required of venture funds. This makes sense in the case of huge global funds, Dona says, but no sense at all in the case of smaller funds, such as those set up under the UK’s Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS). These funds are required to list anything of benefit to the manager or investor, but are not allowed to take account of the fact that EIS funds come with tax breaks.

On a global level, the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) has published a good-practice guide for fees and charges of collective investment schemes. It notes that cost transparency by itself will not always be sufficient to ensure good outcomes for clients, because of the possibility of conflicts of interest.

Among its examples of good practice are: the disclosure to investors of fees and charges ahead of their making an investment; performance fees reflecting the equitable treatment of all investors; the removal of incentives to fund managers to take excessive risk in the hope of increasing their own remuneration; the disclosure to investors of the existence of performance fees and the impact they will have on investor returns, and the provision of information in a form that is clear, concise and not misleading.

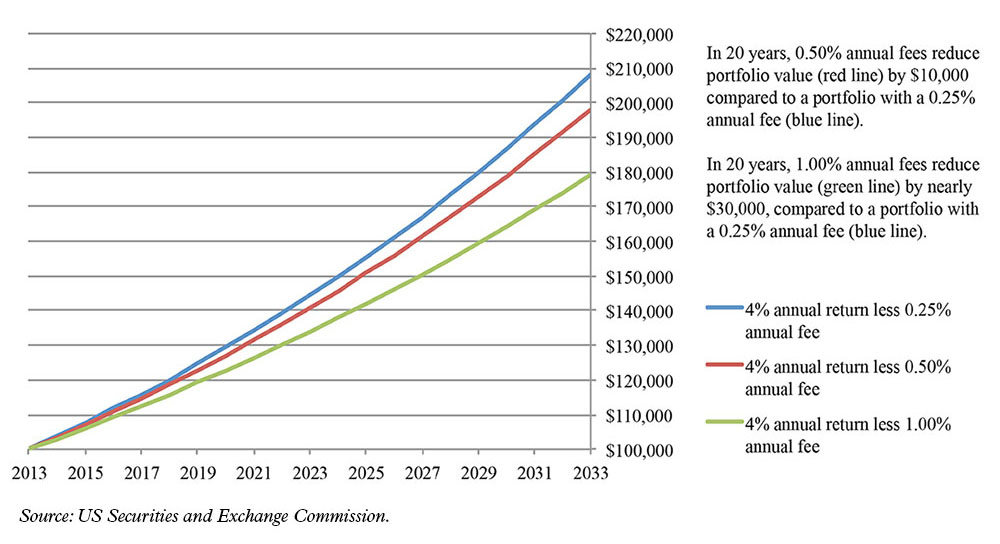

In the US, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) warns in an investor bulletin dated June 2019 that an apparently small difference in terms of charges for collective investment schemes can have a large effect over the long term. Although the bulletin is four years old, It illustrates the effects of charges over the long term, using a notional US$100,000 portfolio invested over 20 years. By the end of that period, an annual charge of 0.5% will have reduced the value of the portfolio by $10,000 compared with a charge of 0.25%.

Portfolio value from investing US$100,000 over 20 years

The example assumes an investment running from 2013 to 2033 with an annual return of 4%. The SEC adds that, while fees and charges may be entirely reasonable, they may still be higher than some investors wish to pay, thus comparison shopping is advised.

Funds are rarely identical

Such an exercise may be complicated by some of the jargon that abounds in the field of fees and charges, with expressions such as ‘total expense ratio’ (TER) and ‘ongoing charges figure’ (OCF). These are less daunting than they appear, with the former being, in effect, a subset of the latter.

The TER represents a fund’s operating costs in relation to its assets. If costs are well controlled, the TER should be lower than if costs are not. Given such costs are withdrawn from the fund, the level of the TER has a direct impact on returns. The OCF takes in the TER but adds in performance fees and one-off charges, thus is a more comprehensive measure.

You may also see reference to “OCF +”, which combines the OCF number with any transaction costs, which are excluded from the OCF.

The Investment Company Institute, a US-based body representing regulated investment funds, cautions against being guided solely by the TER and OCF. In a fact sheet for investors, it says: “If two funds were identical, except for the fees and expenses they charge, the lower-cost fund would be a better option. But rarely, if ever, are funds identical.

“For example, equity funds typically cost more than bond and money market funds, but equity funds historically have provided a significantly higher long-term return – even after expenses are deducted.”

For transatlantic investors, the difference between British and US expressions describing the same thing can be confusing. Helen Ayres, head of communications at the Investment Association, a UK trade body and industry voice for investment managers, cites two examples: ‘one-off charges’ in the UK are called ‘shareholder fees’ in the US, and ‘ongoing charges’ in the UK are ‘annual fund operating expenses’ in the US, she says.

Where does the debate on charges go next? In the UK, the FCA surveyed the landscape in the wake of the 2019 report and is not entirely happy with what it has found. In July 2021, it published a multi-firm review that says that funds are required to report on whether fund fees are justified in terms of value provided to investors.

Positive returns not necessarily good value

Many of the 18 fund managers that the FCA visited as part of the review had not implemented such reporting and some that had were doing so incorrectly. Some, said the FCA, made unjustifiable assumptions while others assessed performance only at a fund level rather than in terms of individual unit classes, thus disguising poor performances at unit level.

Furthermore, many firms failed to consider what the fund should be delivering given its investment policy, strategy, and fees. These firms often judged the value provided by comparing it with the fund’s stated objective. This was regardless of whether this objective reflected how the fund was managed, and what its fees suggested the fund manager ought to be trying to achieve.

The FCA said: “This was particularly apparent for funds that charged a fee commensurate with active management (i.e. with the aim of outperforming market returns), and were managed with the aim of outperformance, but had a more limited stated objective of achieving ‘long-term capital growth’, or similar wording.”

The good news was that many firms had cut fund fees following value assessments, although less attention had been paid to costs for asset management and distribution services. The FCA warns that it will expect a tighter focus in these areas, with firms examining whether the fees charged are justified.

Finally, the FCA suggests investors should not rely on the independent directors that all authorised firms are required to appoint to keep a close eye on fees, as some seem uncertain of the rules and are unable to provide a “robust challenge” to the firms concerned.

Should charges be standardised?

At the European level, EU Commissioner for financial services Mairead McGuinness fired a warning shot in a speech in November 2022. Excessive costs and fees, she said, could significantly reduce returns, something that investors may not fully understand. She adds: “The Commission will consider whether we need to clarify the rules in this area.”

Across the Atlantic, fees are also under the spotlight. In March 2022, William Birdthistle, director of the SEC’s Division of Investment Management, speaking in Washington, said that he was dissatisfied with the information supplied to investors. It was striking, he said, that banks, credit card companies, mortgage providers and car-loan businesses provided single, uniform statements of the fees they charged. “How is it that there is no comparable requirement for statements on the individualised costs for all those trillions of dollars in life savings vouchsafed to investment companies?” he asked.

One response to the continuing controversies surrounding fees and charges would be to standardise them, either nationally or even internationally. But this would go against the grain of present policy, which stresses transparency and disclosure as the spurs to greater competition and lower charges. There may be legal obstacles, too. In the UK, in 1989, a maximum commission agreement among suppliers of packaged financial products was abolished by the then regulator, the Office of Fair Trading, on competition grounds. The agreement limited the scope of commission payments to those selling such products.

The Investment Association has thrown its weight behind greater transparency and clarity in terms of fees and charges. It says in a statement that information about product charges and transaction costs “that answers the question ‘What am I paying?’” ought to be in as simple and accessible a form as possible.

The statement adds: “This means headline numbers and not complex approximations based on multiple assumptions. The information provided to investors must be meaningful and the methodology should not produce results that are misleading to investors.”

Few would disagree with that sentiment.