Andrew Jacobs, a lead consulting partner at legal services business DWF, shares his views on the FCA’s upcoming Consumer Duty rules and what firms should be doing to prepare

by Fred Heritage

Please briefly explain the new Consumer Duty rules. What are they, and what’s their main purpose?

The FCA’s Consumer Duty rules were first outlined during 2021/22, ratified in 2022, and will come into effect throughout 2023. They are for financial services and insurance firms that regularly deal with retail clients and consumers. The FCA is introducing new rules in response to perceived areas of consumer harm and to several issues and challenges it has observed in the financial services sector related to consumer harm as a result of dealing with regulated firms.

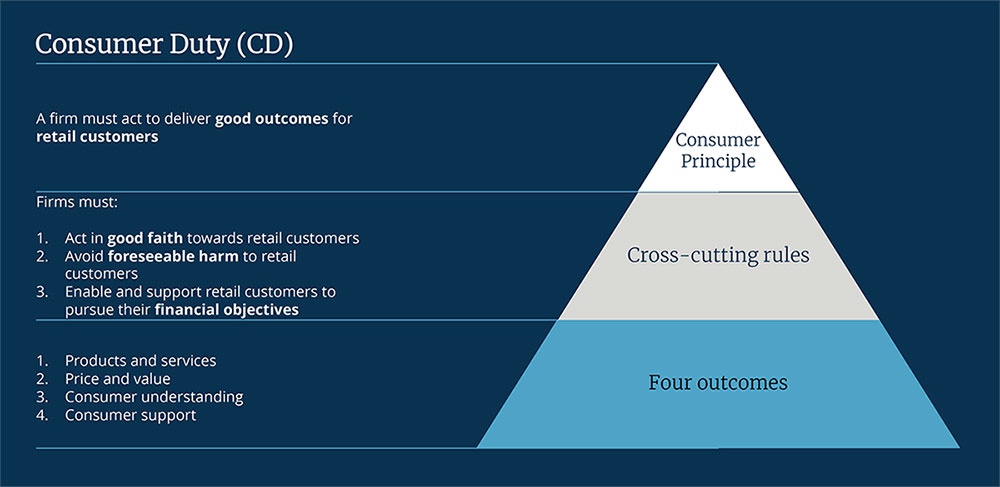

The Consumer Duty rules are built across three tiers. The FCA uses the image of a pyramid to demonstrate these visually. The ‘headline’ aspect (the top of the pyramid) is the Consumer Principle, which dictates that regulated firms must act to deliver ‘good outcomes’ for their retail customers. This will form a new FCA Principle for Business, underpinned by the FCA threshold conditions to which regulated firms are subject, concerning resources (financial and non-financial), the nature of services they offer and how they offer those services to the marketplace. And lastly, the transparency of the business and its arrangements.

Source: DWF

The FCA’s Principles for Businesses go further by outlining the type of conduct expected from any regulated firm. The introduction of new rules means that there'll now be a twelfth principle, in addition to the existing 11. This new Consumer Principle sets out very clearly and explicitly that firms must act to deliver good outcomes for retail customers.

Who are the Consumer Duty rules meant to help?

They are primarily for the benefit of the retail customers of regulated financial firms, whether they’re professional investors or not. Over the past two to three years, it’s come into much sharper focus that it’s retail consumers who have more to lose – or can be impacted potentially most harmfully – by the outcomes of poor financial services conduct, or simply by products and services not performing as they were given to expect. Moreover, it’s consumers who are in difficult or financially vulnerable circumstances, or who are on the threshold, who can least afford to be losing money or be disappointed by the underperforming products and services of financial firms. The new rules, and the new Consumer Principle in particular, are designed to signpost and make clear what the expectations of firms are in relation to the duty of care that they must show retail customers and place an emphasis on firms checking that not only do consumers understand what they are buying, but that price and value are fair and that there is appropriate follow-up on consumer outcomes throughout the lifecycle of products and services.

Why is Consumer Duty needed now?

The FCA has always been concerned with delivering good outcomes to customers and this is one of its primary objectives, but the issue is now particularly pertinent given the UK’s current economic environment, with high inflation and challenges around the cost of living. The past few years have seen a shift in the tone of regulation coming from the FCA, and I think the regulator is becoming slightly more protectionist in its views on financial services, products, markets, and the impact on consumers.

Since 2013, the UK has been operating in the ‘twin peaks’ environment of outcomes-based regulation, in which firms can determine themselves how they respond to the FCA’s rules and guidance. I would posit that across many different areas, the FCA’s expectations have not been particularly prescribed, and therefore different approaches by firms have led to different outcomes in how they demonstrably treat customers fairly.

How are ‘good outcomes’ for customers defined under the Consumer Duty rules, and how can they be realised in practice?

Previous FCA guidance had not made it overly clear about the expectations of how firms should deliver good or fair outcomes to consumers. It was not explicit to market participants what good outcomes were supposed to look like across each sector and that has been one of the strongest drivers for the introduction of Consumer Duty – to introduce evidential expectations.

There’s an opportunity here to pivot and really stand out as leaders in your field

The new Consumer Duty framework sets out several expected consumer outcomes and includes three ‘cross-cutting’ rules, providing three clear principles about how firms should behave to deliver outcomes that are fair or good. These state that firms must act in good faith towards retail customers, must avoid foreseeable harm to customers, and must enable and support customers to pursue their financial objectives.

Then, at base level (of the pyramid), the Consumer Duty prescribes four outcomes. Firms must demonstrate that they are behaving in ways that are fair or good by providing evidence through outcomes relating to products and services, price and value, consumer understanding and consumer support. Now, the burden of proof is on firms to evidence how they are delivering the Consumer Duty outcomes.

The Consumer Duty rules are due to come into force in July 2023. What practical steps should firms have taken ahead of that date?

There are several. Our approach has six steps. First, by the end of October 2022, all regulated firms were required to make sure they had an implementation plan outlined. This only needed to be a high-level plan, outlining the steps firms were planning to take. It didn't necessarily need to be granular or detailed, but had to be signed off by the governing body of each firm. At DWF, we have a clear view of what that implementation plan should contain and how it should have evolved since October. We encourage firms to follow our methodology and revisit their plan, to ensure that the analysis about how their firm is likely to be impacted by the Consumer Duty is still sound, and that they've looked at the application to their business holistically, thoroughly, and in detail. At the time, I think some firms were a little shocked by the expectations around the implementation plan, and rushed to meet the October deadline. Now, firms have had a little time to reflect and check their plan to make sure that it has clear workstreams and sets out the appropriate milestones in the areas it needs to address.

The second stage of preparing for Consumer Duty, in our opinion, is to look at the design of the Consumer Duty framework in relation to your firm. How will your firm demonstrate that its products and services are offering fair value, that they are targeted to the right consumers, and are being distributed at their intended cost point? Each firm should think about a matrix approach as part of the overall framework to demonstrate this. Also, firms need to consider how they will prove to the regulator, through evidence, that customers are receiving good outcomes on an ongoing basis. Partly, this involves designing new processes. But it’s also about looking at existing controls and systems and judging if they can provide some of what's needed in terms of the necessary evidence. Recent ‘Dear CEO’ letters have stressed the needs for firms to prioritise, not underestimate the time it will take to consider the end-to-end distribution chain, and to not forget about cultural drives to reinforce behaviours expected under the Consumer Duty.

We have a clear view of what a Consumer Duty implementation plan should contain and how it should have evolved since October Step three is focusing on the ‘build’ phase of the Consumer Duty framework over the next three to five months. Firms need to ensure they have the necessary controls, systems, and monitoring in place, and look at counterparties in the distribution chain to understand that, at every step, the firm can deliver the end cost and value that consumers can expect and that there aren't any weak links in the chain.

As a fourth step, DWF recommends implementing a ‘proof of concept’ phase. Firms should give themselves one or two months to consider if these processes work in reality. Begin testing and piloting these processes behind the scenes, before you're placing reliance on them, to ensure they do the job that's needed and will deliver what customers should be able to expect. They also need to demonstrate your firm’s compliance to the regulator.

Then, we'd recommend you go for the hard launch, stage five. This should include making sure that communications to customers are clear and that they understand what they are required to know under the Consumer Duty, and should go beyond the foundations of being clear, fair, and not misleading. Firms need to be able to communicate (as well as demonstrate) that they're acting in consumers' best interest, giving them good outcomes and acting in good faith, while avoiding foreseeable harm. The hard launch is also about ensuring that, internally, every individual at the firm who has a role in the customer journey, or is involved in any aspect of supporting the Consumer Duty, is clear about their role and involvement in delivery. They need to be ‘living’ the Consumer Duty, so that it is adopted into the business post-launch and can be embedded effectively.

Your firm’s internal controls need to be able to check that processes are happening effectively. Whether that’s the people on the frontline, who are dealing with customers first-hand, or involved in second-line, monitoring to make sure the right outcomes are happening, or functions such as internal audit, which is all about taking an objective view of the whole process to confirm that each part of the control framework is working properly. Each of the three lines has a role to play. Step five, the launch, should be relatively straightforward if you've taken every other step in the process.

Then, step six should be the ‘embedding’ of Consumer Duty on an ongoing basis. This will involve reviewing regulatory feedback and thematic work, looking at changes to your business as your customer base changes, and looking at the macro environment you’re operating in as well as some of the micro drivers. Firms will want to perform immediate testing post-implementation and then at appropriate intervals after the launch to make sure the Consumer Duty framework is performing as expected, and make any tweaks or updates so that it remains fit for purpose.

What are the advantages of Consumer Duty over the long term, for customers and firms?

The advantages for firms over the long term are somewhat subjective, but there are some. The first is that the financial services sector, and financial advice and products, have continually been plagued with different types of scandal and criticism about how they’re offering value or transparency to consumers, and to retail markets in particular. Consumer Duty will allow the sector to go further towards demonstrating professionalism and to reverse the negative reputation that some ‘bad actors’ may have given to the sector.

There's an opportunity to raise standards and bring greater trust and transparency into financial services generally. It will emphasise that strong compliance can benefit firms, and be a unique selling point as part of an overall client proposition, not just a cost. Compliance can be something for firms to market based on their standards, transparency, and levels of customer service and satisfaction. For firms that implement Consumer Duty well, there’s an opportunity here to pivot and really stand out as leaders in their field.

Are there any further challenges that firms could face when implementing these rules?

Many firms will already have decent mechanisms for looking at price, value, and customer expectations for how their products should perform. Some will be further along than others in terms of being able to use existing requirements to achieve what's required under the Consumer Duty. Many firms were involved in the Retail Distribution Review (RDR), for example. So areas such as pricing, when it comes to advice services, should be relatively straightforward for them.

A problem could arise for firms who were not greatly touched by regulations such as the RDR. They may have many customers who are charged completely differently when it comes to their portfolios, particularly in relation to discretionary advice or portfolio charging, because of existing relationships or legacy issues. The biggest challenge for these firms will be moving the sheer volume of customers to a place where there's consistency and a harmonious approach to factors such as pricing and value.

I'm hopeful that the FCA will start giving more trust back to firms as milestones are met A big challenge for some firms will be unravelling some fee structures and moving towards commonality. I think every firm will benefit from the simplicity of knowing they perhaps have two, three, four, or five different pricing structures, instead of 100, in the business.

So, the volume of processes to change will be challenging for some firms, as well as the time and resources necessary to implement the Consumer Duty. When looking across different aspects of the financial services spectrum – more so in the insurance space – it will be challenging for those handling legacy or closed-book products to demonstrate aspects of the Consumer Duty like fairness and value. Those have the potential to be significant challenges.

At the same time, the regulator has issued considerable guidance, and the devil is in the detail. At DWF, we spend a lot of time looking at the FCA’s rules and guidance, together with ‘Dear CEO’ letters and engaging with the regulator. Most publications include numerous helpful expectations and steers about how to navigate these challenges. So, help and advice for firms is out there if they’re seeking it.

How might the Consumer Duty change firms’ relationship to the FCA going forward?

About the expert

Andrew Jacobs leads DWF's regulatory consulting offering globally.

He has been a regulatory professional for 20 years, working across different areas of the financial services sector, both in the UK and internationally, and has provided advice to clients based on UK and home state regulations in jurisdictions including Australia and Singapore.

Andrew has been a partner at two top ten accounting firms, helping to develop their consulting practices. He has held positions on the board at several wealth, advisory and distribution firms, where he has been FCA approved for having responsibility for compliance oversight, training and competence, risk and anti-money laundering.

The FCA, and financial services regulation in the UK generally, is in a very interesting place. On one hand, you have the FCA moving into a more protectionist role when it comes to consumer outcomes, and I empathise and understand why that is. Many people in the UK are on low incomes. They can't afford not to have their expectations met by the financial services market in the current economic environment. Providing more of a roadmap for regulation is the right thing to do to make sure these outcomes are being met, and consumers are getting a fair deal.

For firms, the Consumer Duty pushes them towards greater regulation. On the other hand, in December 2022, the Treasury announced the Edinburgh reforms, which will look at whether it’s necessary to review and repeal certain areas of financial regulation, such as the Senior Managers and Certification Regime. These are two competing narratives which may prove confusing for firms, but continuing to do the right things for consumers will never be academic, regardless of how regulation changes.

At the same time, there’s a void in the regulatory landscape because Brexit legislation and rules haven't come to pass. The FCA hasn't moved quickly enough to ‘onshore’ its home state regulations. And yet, at the same time, some retail banks with account holders in Europe are cutting ties with them, because there's no way to continue dealing with them. So, the relationship between the regulator and firms is currently quite complex.

Based on what I’ve seen of the Consumer Duty plans, and the thematic follow-up and supervision work that will take place, I'm hopeful that the FCA will start giving more trust back to firms as milestones are met, and have greater faith that they’re trying to do the right thing, but do sometimes need clarity of expectation to get it absolutely right in the eye of the regulator. If the supervisory follow-up is proportionate and helpful, the FCA can be a force for good in guiding firms and ensuring that consumers can achieve their financial goals, at a fair price that firms can deliver, with appropriate levels of protection.