Some critics are anti-ESG evangelists. Others have legitimate concerns. Advocates need to build the ESG case more robustly.

by Paul Bryant

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing is being criticised on multiple fronts. It has been caught up in US culture wars, greenwashing scandals, waning investment performance, and problems with defining, measuring, and applying ESG metrics.

While some politically-motivated anti-ESG views border on conspiracy theory (such as accusing BlackRock of trying to implement a social engineering project – see below), there are legitimate, albeit not always definitive, criticisms in some of the anti-ESG arguments.

Charles Radclyffe, CEO of EthicsGrade, a specialist ESG ratings agency focused on digital ESG risks, says there is a tendency among ESG advocates to dismiss criticisms. “It’s time to step out of our ESG echo chambers, engage with critics, and drive the movement forward,” he says.

We examine the severity of the backlash, and the cases for the prosecution and defence.

ESG capital flows down but not out

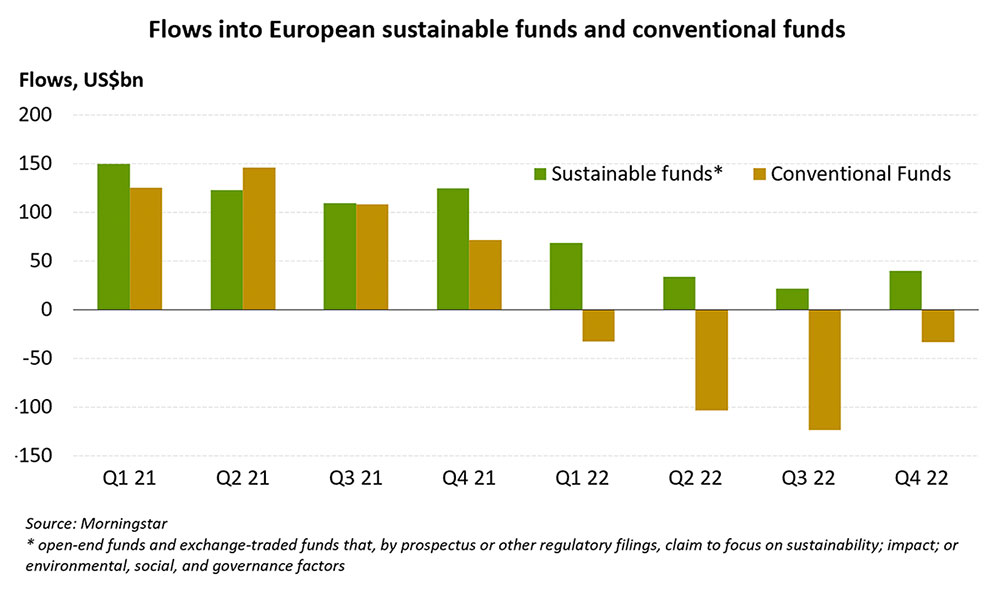

Capital flows into ESG investment funds fell dramatically in 2022. But not nearly as dramatically as the wider fund landscape, which suggests that ESG investing, while experiencing high-profile and concerning headwinds, is certainly not undergoing an existential crisis.

In Europe (including the UK), by far the dominant sustainable investing market with 83% of global sustainable fund assets, according to Morningstar’s Global sustainable fund flows: Q4 2022 in review report, flows into sustainable funds remained positive in every quarter of 2022, in stark contrast to conventional funds which saw outflows in every quarter.

In the US, the second-largest market with an 11% share of assets, capital flows were also stronger than the overall fund market.

In 2022, net capital flows into sustainable funds were small but still positive (+US$3bn), unlike the overall US fund market which recorded net withdrawals of −US$370bn, according to Morningstar’s Sustainable funds U.S. landscape report.

But those annual statistics mask the declining situation over the course of the year. Nearly all the positive flows in the US were recorded in Q1 of 2022, with Q4 recording heavy outflows.

The starker decline in US flows compared with Europe coincided with a ramping-up of a vocal anti-ESG movement, suggesting a backlash in the US is starting to bite.

US concerns extend beyond ‘war on woke’

ESG has become an intense battleground in the US. Some arguments mix political ideology with challenging the financial credibility of ESG investing. In December 2022, announcing that the state of Florida would be divesting US$2bn from BlackRock for its pro-ESG stance, Florida chief financial officer Jimmy Patronis said: “Using our cash … to fund BlackRock’s social engineering project isn’t something Florida ever signed up for. It’s got nothing to do with maximising returns and is the opposite of what an asset manager is paid to do.”

Other arguments are based on the impact ESG could have on the oil and gas industries. In Texas, a law was introduced in 2021 which requires state entities to disinvest from companies (including investment funds) that boycott energy companies. In March 2022, Texas comptroller Glenn Hegar said: “Numerous companies and their leadership are pushing an environmental agenda that not only threatens the Texas economy and jobs, but also undermines national security.”

The movement is gaining momentum. In response to the 2022 Department of Labor rule that allows fiduciaries to consider ESG factors when they select retirement investments, 25 Republican states filed a suit in January 2023 in an attempt to block the rule.

And in February 2023, Republicans set up a Financial Services Committee Republican ESG Working Group to: “protect the financial interests of everyday investors, … combat the threat posed to our free markets by far-left environmental, social, and governance proposals, … [and] examine ways to rein in the SEC’s [Securities and Exchange Commission] regulatory overreach” (presumably referring to actions such as SEC proposals to enhance ESG disclosures).

ESG = higher returns. Not so fast.

Outside of political circles, the debate around ESG’s investment return potential has also escalated.

Prior to 2022, claims were common that ESG investing produced superior returns, or at the very least, not inferior returns. In a 2021 report, ‘Why sustainable strategies outperformed in 2021’, Morningstar says that over a five-year period, seven out of ten of its US sustainability indexes beat their benchmarks.

But it was a different story in 2022. Resource companies, shunned by most ESG funds, outperformed sectors favoured by ESG funds. Morningstar’s February 2023 Sustainable funds U.S. landscape report states that “most sustainable funds underperformed on nearly every metric in 2022.”

Most pre-2022 studies fail to mention that excess returns mostly resulted from high exposure to large-cap technology companies, which outperformed, says Professor of Finance at NYU Stern, Aswath Damodaran, a vocal critic of ESG investing. This, he says, was mostly based on a highly simplistic view that because they didn’t have obvious smokestacks, these companies could be ‘sold’ to investors as being good for the environment: “When the ESG boom took off, big tech was an obvious stock market play which ESG funds took advantage of. There was hardly any robust analysis of sustainability”.

He says that ESG is bound to underperform over time: “Simple mathematics dictates that constrained portfolios, which is what ESG investing is, must underperform over the long term because their unconstrained counterparts simply have more companies to choose from.”

Some of the most credible advocates of sustainable investing, such as Julie Gorte, senior vice president for sustainable investing at Impax Asset Management, which has a 25-year track record in the area, acknowledge that there isn’t a definitive answer to the question of ESG returns. “Every asset class underperforms sometimes, as ESG did in 2022. But I’m confident that the transition to a low carbon economy is going to be a long-term value driver for many businesses. I don’t think the short-term impact of the war in Ukraine is going to be a long-term value driver for non-sustainable stocks, as it has been over the past year.”

She also counters the constrained portfolio argument: “All portfolios are constrained. If you only invest in equites, or a geographic region, or growth stocks, you are constraining your portfolio.”

Greenwashing concerns linger

Many ESG funds have opened themselves up to a greenwashing backlash, after using ESG more as a marketing tool than as a mechanism to bring about better ESG practices in investee companies.

One of the higher-profile cases occurred at Deutsche Bank’s asset management arm DWS after its former chief sustainability officer alleged that the company inflated its ESG credentials. According to Bloomberg, prosecutors found that “contrary to the statements in the sales prospectuses of DWS funds, ESG factors actually only played a role in a minority of investments.”

But regulators in the major markets appear to be addressing this issue. In the EU, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation continues to roll out, with regulatory technical standards in effect since January 2023 that require asset managers to improve sustainability disclosures. In November 2022 the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published a call for evidence on greenwashing practices in the EU financial sector, and the ESMA consultation on guidelines for tightening restrictions on the use of ESG or sustainability-related terms in funds’ names closed on 20 February 2023.

Similar initiatives to enhance ESG disclosures are underway in the UK, with the Financial Conduct Authority’s Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR) and investment labels consultation paper and in the US, via SEC proposals to enhance ESG disclosures.

Difficulties measuring ESG hurts credibility

Measuring ESG credentials is another area of criticism. In a 2022 paper, Aggregate confusion: the divergence of ESG ratings, Berg, Kölbel and Rigobon compare six major ESG ratings companies and find that ratings and conclusions differ substantially between them, with consequences including: difficulties evaluating and comparing companies, funds, and portfolios; companies receiving mixed signals from rating agencies about which ESG actions are expected and valued by the market; and difficulties linking CEO compensation to ESG performance (CEOs may optimise for one rating and underperform on others).

Simon McMahon, global head of ESG research products at ESG ratings company Sustainalytics, says that measurement scrutiny has come from two main groups: “First, financial services companies and regulators who are pushing for the maturation of ESG and looking for better metrics. That is healthy pressure and welcomed. Second, from die-hard ESG critics, who are concerned about the burden additional disclosures place on companies. And much of this scrutiny is not intended to be productive, it is intended to shut down ESG.”

But there’s no doubt the ratings landscape has undergone a huge leap in sophistication. Simon points to Sustainalytics’ risk ratings which now cover many more ESG-related risks than previously (such as risks in supply chains), quantitatively evaluates the degree of exposure to that risk, and then assesses how management is dealing with it. Previous ratings only allowed for comparisons within a sector, but now allow for cross-sector comparisons – so the emissions of a manufacturer can be compared to those of a technology company (which are often less obvious – such as the emissions from powering large scale data centres, which are very power-hungry).

But Simon does acknowledge there is still progress to be made. He says: “The raw data we access is often incomplete, inconsistent and of low quality. But it’s our job to verify that data and put it into useful frameworks. The quality of data is improving all the time though, as is our use of it.”

No obvious backlash in other markets

Sammie Leung, partner – regional ESG services PwC Asia Pacific, says that ESG investing in both Hong Kong and Singapore is on an upward trajectory, but a little behind Europe in terms of market maturity.

She says there is virtually none of the anti-woke, anti-ESG arguments in either of these markets nor any major backlash against greenwashing, although individual cases certainly exist. She says: “The greenwashing debate is mostly about if individual investments match up closely enough to an ESG fund’s mandate and not so much about asset managers misleading investors. But I think upcoming regulation will help to resolve some of these debates.” She cites as an example the Green and Transition Taxonomy, which is being designed in Singapore. Sammie says that a taxonomy makes product design easier and should reduce greenwashing controversies.

In India, according to Sambitosh Mohapatra, partner and leader – ESG platform/energy utilities and resources at PwC, the debate around ESG is all about equitable growth, managing stakeholder expectations, driving business outcomes and aligning with the reporting regulations, with no signs of a backlash.

He is bullish on India’s transition to a lower carbon economy leveraging its old civilisational roots or Indian way of life. He sees an interesting play in India between policy measures and regulatory requirements with market needs and social feedback. For example, he says there is huge momentum building around the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s Lifestyle for Environment (LiFE) initiative. This involves driving four primary shifts in India: nudging individuals and industries to practice more environment-friendly actions (such as mindful and deliberate consumption); enabling usage of energy efficient technologies, transitioning to renewables for energy needs; and creating a carbon market for offsetting. He says: “I have been overwhelmed by the response of the communities and companies to these policy measures to transition their operations and supply chains. It has become a CEO agenda now.”

In South Africa, the ESG movement is also building momentum although, according to Asief Mohamed, chief investment officer of Aeon Investment Management, adoption is still in its early days. He says: “It got off to a slow start with some resistance from investment companies and analysts. Many didn’t, and some still don’t, see ESG as part of fundamental analysis, but rather as an additional burden on investment analysis. But I wouldn’t say there’s a backlash.”

Growing pains or existential threat?

Some reckon ESG investing will unravel entirely. Professor Damodaran says: “All it does is put pressure on a subset of companies – public companies. We can’t ask capital markets to do what laws, regulation, and consumer action (such as changing buying habits) should be doing. If we rely on capital markets to effect change, all that will happen is polluters will go private.”

But Julie Gorte thinks it will only ramp up: “Sustainability and climate risk issues will be used by all sophisticated investors over time because it’s so obvious that they’re financially material. And as millennials and gen Zs get older and wealthier, they will put more of their investments into sustainable portfolios compared to previous generations.”

While ESG investing is certainly under fire, especially in the US, current trends suggest it is undergoing growing pains, rather than an existential threat.